Posted in Legislative Research on Jul 29, 2019

The Amyotha Hluttaw is currently discussing an Aquaculture Bill drawn up by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MoALI). The earlier law was approved in 1989, so it is the first time in 30 years the overarching legal framework for aquaculture has been reviewed.

The Amyotha Hluttaw is currently discussing an Aquaculture Bill drawn up by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MoALI). The earlier law was approved in 1989, so it is the first time in 30 years the overarching legal framework for aquaculture has been reviewed.

The Bill aims to achieve sustainable development of aquaculture, prevent the extinction of fish resources, preserve fish eco-systems, support fisheries with clear regulation, and enable fishery research and the spread of technical know-how.

Fishery in Myanmar

The definition of ‘fishery’ tends to include both freshwater and marine fisheries, and related operations. Freshwater fisheries may be aquaculture, leasable and open fisheries; and marine fisheries are both inshore and off-shore. Various fishery-related operations provide inputs to the fisheries, including the production of fish seed (fertilized fish eggs), fish feed, ice, and boat rental; whilst operations downstream of the fishery include processing, packaging and transport.

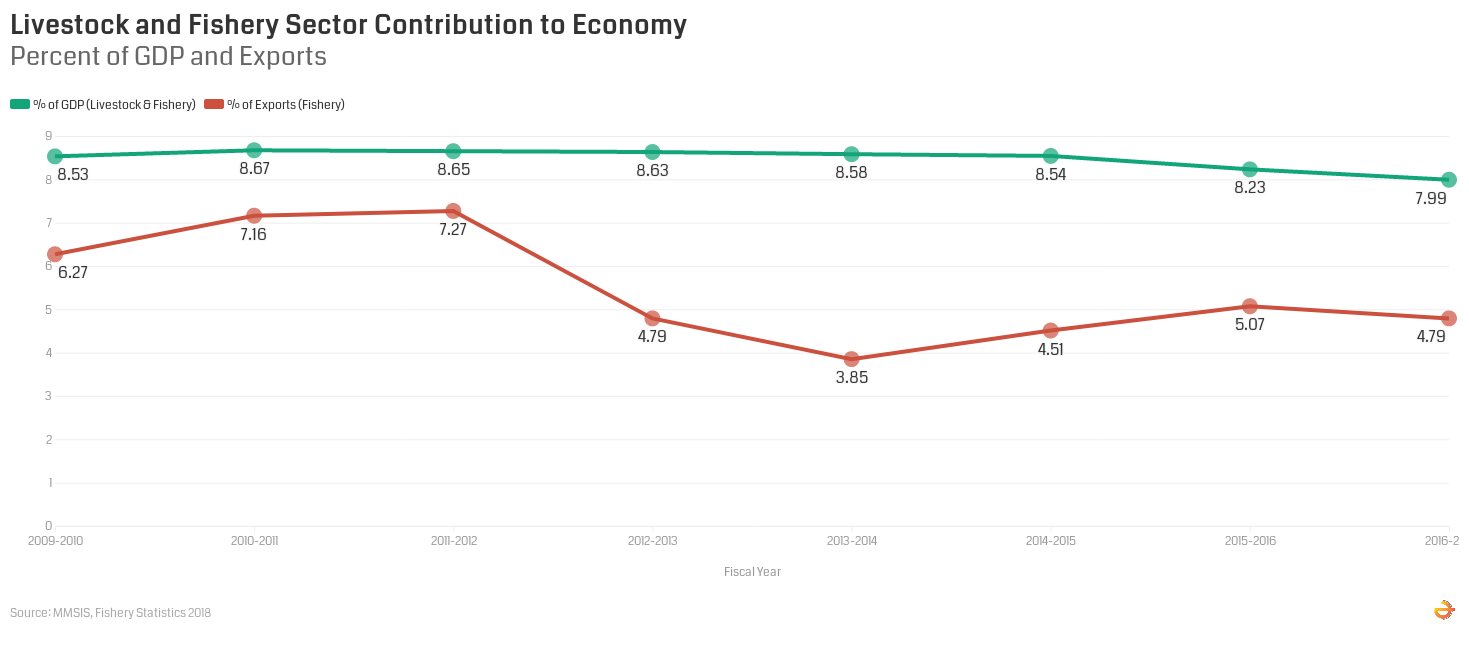

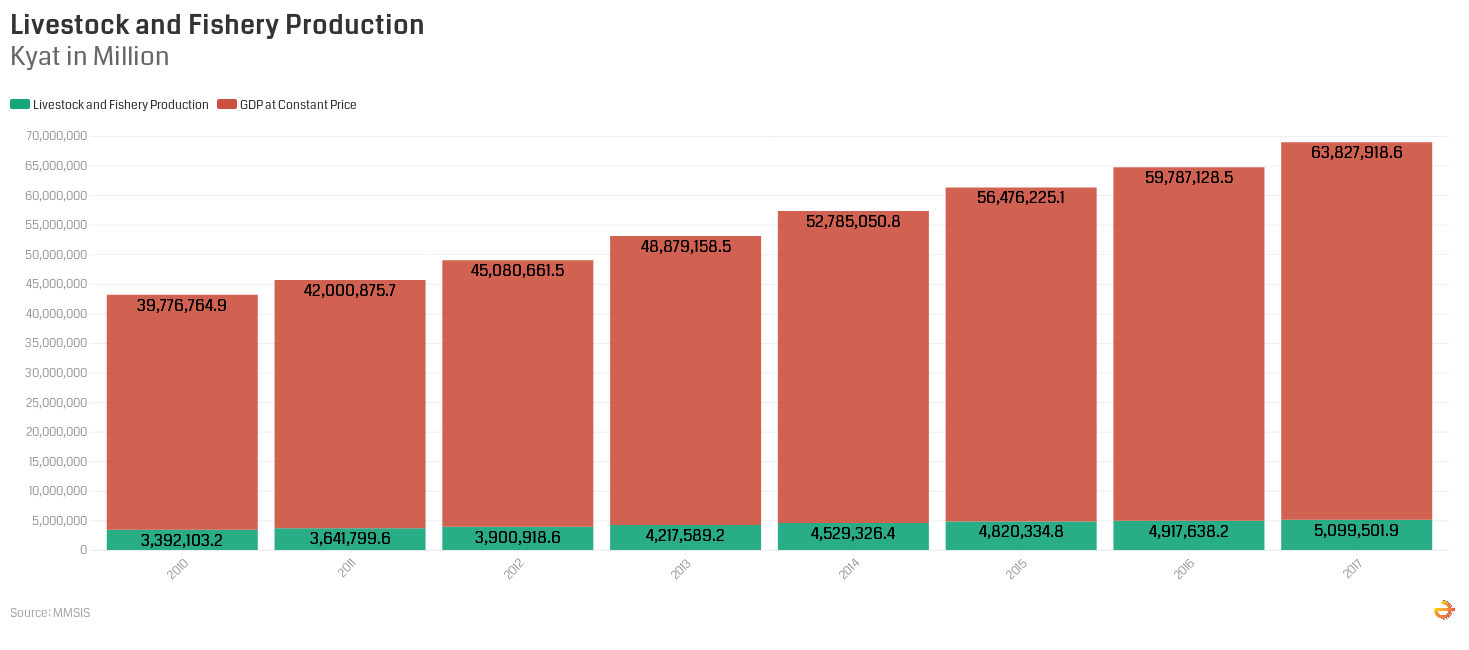

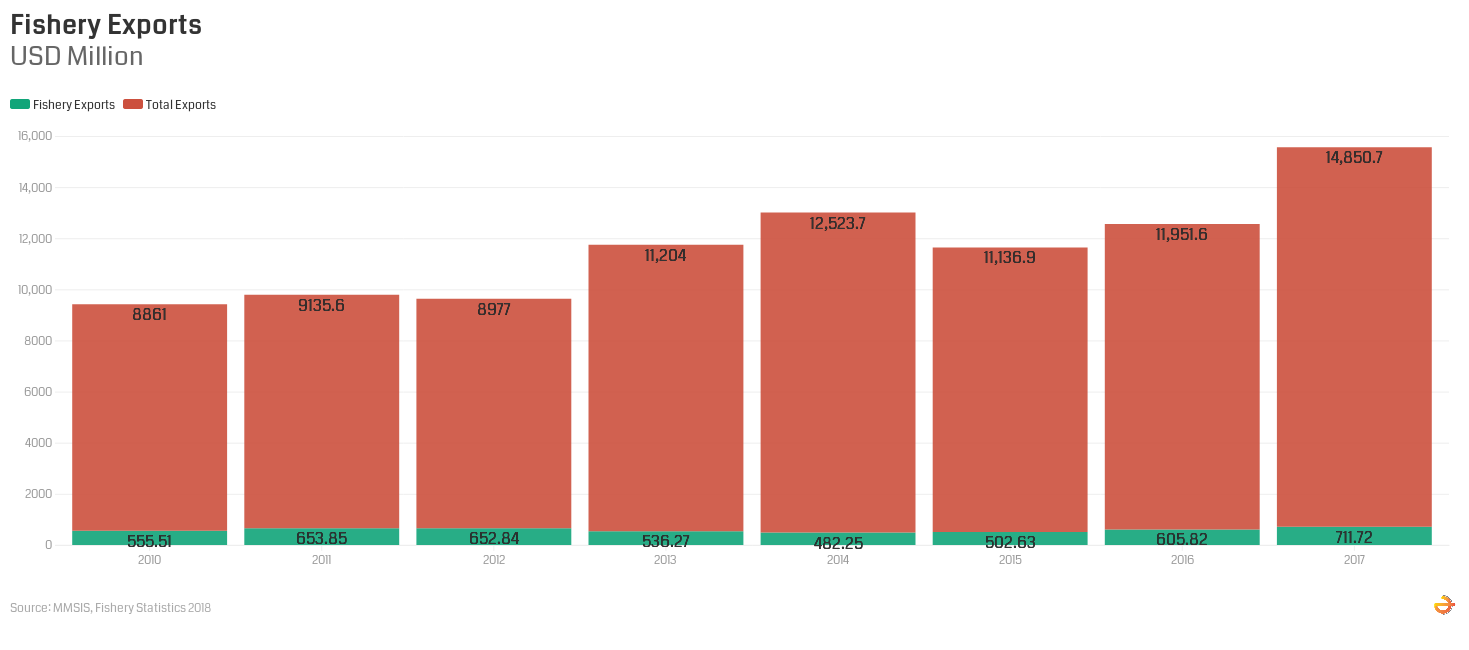

Myanmar’s fisheries contribute a sizeable proportion of the country’s exports, and make an important contribution to GDP. According to the Central Statistical Organisation, livestock and fisheries contributed 8.53% of national GDP in 2010-11, and 7.99% in 2017-18. Although the percentage contribution has declined, this can be explained by relative growth in other sectors, as livestock and fisheries have actually seen a real increase in output. In term of exports, fishery exports were 6.27% in 2010-11, and 4.79% in 2017-18. Again, in spite of a percentage decline there has been an increase in fishery exports.

Myanmar’s fisheries contribute a sizeable proportion of the country’s exports, and make an important contribution to GDP. According to the Central Statistical Organisation, livestock and fisheries contributed 8.53% of national GDP in 2010-11, and 7.99% in 2017-18. Although the percentage contribution has declined, this can be explained by relative growth in other sectors, as livestock and fisheries have actually seen a real increase in output. In term of exports, fishery exports were 6.27% in 2010-11, and 4.79% in 2017-18. Again, in spite of a percentage decline there has been an increase in fishery exports.

Fisheries provide an important source of income for rural populations and so their development can be positively associated with economic development and poverty reduction. Myanmar has therefore previously sought to pass laws in an attempt to put the industry on a firmer footing and allow for its sustainable growth. At Union level the laws relating to fisheries are the Fishing Rights of Foreign Fishing Vessels Law 1989, the Aquaculture Law 1989, the Myanmar Marine Fisheries Law 1990, and the Freshwater Fisheries Law 1991. The 2018 Constitution delegates responsibility for inland fishery legislation to the States and Regions, and each of them has in place their respective Inland Fisheries Laws.

Fisheries provide an important source of income for rural populations and so their development can be positively associated with economic development and poverty reduction. Myanmar has therefore previously sought to pass laws in an attempt to put the industry on a firmer footing and allow for its sustainable growth. At Union level the laws relating to fisheries are the Fishing Rights of Foreign Fishing Vessels Law 1989, the Aquaculture Law 1989, the Myanmar Marine Fisheries Law 1990, and the Freshwater Fisheries Law 1991. The 2018 Constitution delegates responsibility for inland fishery legislation to the States and Regions, and each of them has in place their respective Inland Fisheries Laws.

Currently, a Marine Fisheries Bill is being drafted to replace the existing Fishing Rights of Foreign Fishing Vessels and Myanmar Marine Fisheries Laws, whilst this Aquaculture Bill has been submitted to the Amyotha Hluttaw to replace the Aquaculture Law 1989.

Aquaculture

‘Aquaculture’ – which generally refers to fish farming, as distinct from fishing in open fisheries – began to be modernised with imported species in 1953 and expanded from 1960 with support from the state.

In 1989 the Aquaculture Law was passed and relaxed certain restrictions facilitating further expansion in the sector. This expansion has continued, with a total aquaculture pond area of 440,585 acres in 2008 increasing to nearly 500,000 acres in 2017. Ayeyarwaddy Region has the greatest pond area, followed by Rakhine State.

The 1989 Law and permitted land for aquaculture

In 1989 the aquaculture law was passed to relax the rules on fish-farming. It has allowed for applications to be made for grants (transfers of land) and licenses (permission to operate fish farms) on aquaculture land, aquaculture water which is not concerned with the government department, and reserved aquaculture water. Here, aquaculture land means land allocated to the Fishery Department by the Union government, in accordance with the existing Farm Land Law and Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law.

2019 Aquaculture Bill

In this Bill, there are two separate chapters concerning the required permits for aquaculture – applying and issuing grants and licenses. In terms of grant application, the Bill describes how to apply for aquaculture land and water managed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation.

Applications for licenses to conduct aquaculture operations must be made for any land/water, including that managed by the Ministry or owned by a government department, or run as a private business. Notably therefore this also includes land allowed for aquaculture by the Central Administrative Body of Farm Land in line with the Farm Land Law, and land allowed by the Central Committee in line with the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands (VFVL) Management Law.

It is in respect of these latter types of permitted aquaculture land where there is a significant difference between 1989 Law and this Bill. The 1989 Law requires the Fishery Department to first acquire farm land and vacant and virgin lands for aquaculture with approval from the government. Once the Fishery Department has acquired the land, only then could another party who wishes to conduct aquaculture apply for the relevant grants and licenses from the Department. However, the new bill says instead that those wishing to conduct aquaculture have to first get a grant for the land from the Central Administrative Body of Farm Land, or from the Central Committee for Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management, and only after that do they apply for a license to the relevant Department Head.

Alternative land use

The Fishery Department aims to increase by 1.3% the average gross output value (GOV) between 2016 and 2020, and recognises many challenges with achieving this targeted growth. One of the challenges is associated with formally allocating aquaculture land. Currently, aquaculture land is estimated at 480,000 acres, of which about 110,000 is legal while the rest - 77% - is illegally conducted on farm land. This is due to difficulties of applying for alternative land use under La Na 39 – application of alternative land use was not seemingly for the aquaculture since farm land for that use had been already transferred to the Fishery Department, and complex bureaucratic procedures.

As for the first difficulty, the change in this Bill seems to tackle it. What the difference between the existing law and the new bill implies is that there will be more than previous permitted land for aquaculture. In other words, this bill will allow the applicant for the grant request as much as the other two committees could give with their own policy, unlike the previous situation where the fish farmers are more likely to conduct the aquaculture illegally as a result of insufficient land allocation by the Fishery Department.

Nevertheless, the second barrier proves to be not easy to be solved. Responding to a question about land being used for aquaculture without applying for an alternative land use designation, the Deputy Minister for Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation told the Hluttaw in February 2018 that “in the past we have considered a fish-farming pond without having applied for this alternative land use to be subject to a fine for conducting aquaculture”. Fines are therefore seen as a temporary measure to punish those illegally conducting aquaculture on farm land.

Main challenge

This draft Bill does not specify any timetable for transition to the new regulations. When and how will new fines be imposed on operators who suddenly discover they are operating illegally? This uncertainty and risk of prosecution is not helpful for the aquaculture industry.

For the government to lift the aquaculture sector, it should move as quickly as possible to implement the process of legalising aquaculture land which has no La Na 39. Strict limitations on the industry should be relaxed, and in the process other relevant land management laws taken into account. We have reported previously at The Ananda on the various ways that new and existing laws relating to land are making the regulatory environment increasingly complex, and therefore increasingly difficult for people to navigate in order to run their fishing or farming businesses (https://theananda.org/en/blog/view/two-new-bills).

Therefore, only when this main challenge is solved, the aquaculture sector can improve as much as possible so as to support the improvement of fishery industry.

The Ānanda

The Ānanda