Posted in Legislative Research on Jul 09, 2019

The Ministry of Commerce has drawn up a new Bill designed to protect domestic producers from the negative effects of increased imports. The Safeguard Bill, which has been submitted to the Amyotha Hluttaw, sets out emergency measures the government may take ‘with respect to increased imports of particular products, where such imports have caused or threaten to cause serious injury to the importing Member's domestic industry.

In this article we take a look at international trade, the nature of trade remedies such as safeguard measures, and review the current Safeguard Bill.

Free Trade

International ‘free trade’ refers to a principle that states that, for markets to function optimally, ‘artificial’ barriers to trade such as interstate trade barriers, or subsidies for particularly businesses or industries, should be avoided. Free trade principles have dominated global trade since the early 20th century, and particularly in the wake of World War II and the neoliberal (Washington) consensus of western nations that led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Proponents of neoliberal, market economics argue that truly free markets will allocate resources in the most efficient way. Thus, government interference through taxation or subsidy is undesirable as it introduces distortions to the market.

Benefits of free trade

Proponents claim that free trade brings beneficial outcomes. They argue that competition drives up the quality of goods and services, drives down prices, creates incentives for innovation, and ensures the efficient allocation of resources.

Drawbacks of free trade

Although there is international consensus on the principle of free global trade, many argue there are significant drawbacks as it allows more powerful and wealthier nations to exploit developing countries, and encourages the removal of safeguards against human rights violations and environmental degradation. (After all, the global free trade model we have today was designed by western nations whose colonial domination was ending, and who were looking for ways to maintain their pre-eminence).

Even within a rules-based free trade framework, there are ways that more economically powerful nations can exploit their position to favour their own industries, often reinforcing inequality between developing and developed countries. For example, a country might ‘dump’ a product into the global marketplace, by selling it a price lower than that charged in their home market. To counteract such practices and limit trade damage, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has devised a series of trade remedies.

Trade remedies

In order for a genuinely free market to operate, there must be clear rules or regulations by which all participants in that market are bound. On the international stage these rules are established by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), principally through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). There are also three main agreements governing ‘trade remedies’, i.e. remedial actions a government may take to protect themselves against instances where exposure to world trade might have a harmful effect on domestic industries. These three agreements are the Anti-Dumping Agreement (ADA), Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM), and Agreement on Safeguards (ASG).

The ADA allows countries to protect themselves if dumping practices (i.e. selling a product or commodity at a price lower than on its own domestic market) can be proven to be causing harm to their own industries.

The ASCM sets out rules for when member countries can and cannot subsidise their industries and allows countries to take actions – ‘countervailing measures’ – to protect themselves against a scenario where another country subsidises their own exports, enabling them to undermine domestic production.

The ASG allows countries to take actions to protect their own industries in the eventuality that a marked increase in imports of products harms the competitiveness of domestically produced goods. It allows countries to levy import taxes on a particular product for a period of time, to allow domestic producers time to adjust.

Safeguard measures are seen as an easier trade remedy to enact than anti-dumping and countervailing measures, because there is less of a requirement to investigate and prove that another country’s actions are harmful. A country simply needs to show that imports have increased, and how the increase has negatively impacted on the relevant domestic industry.

Situation in ASEAN member countries

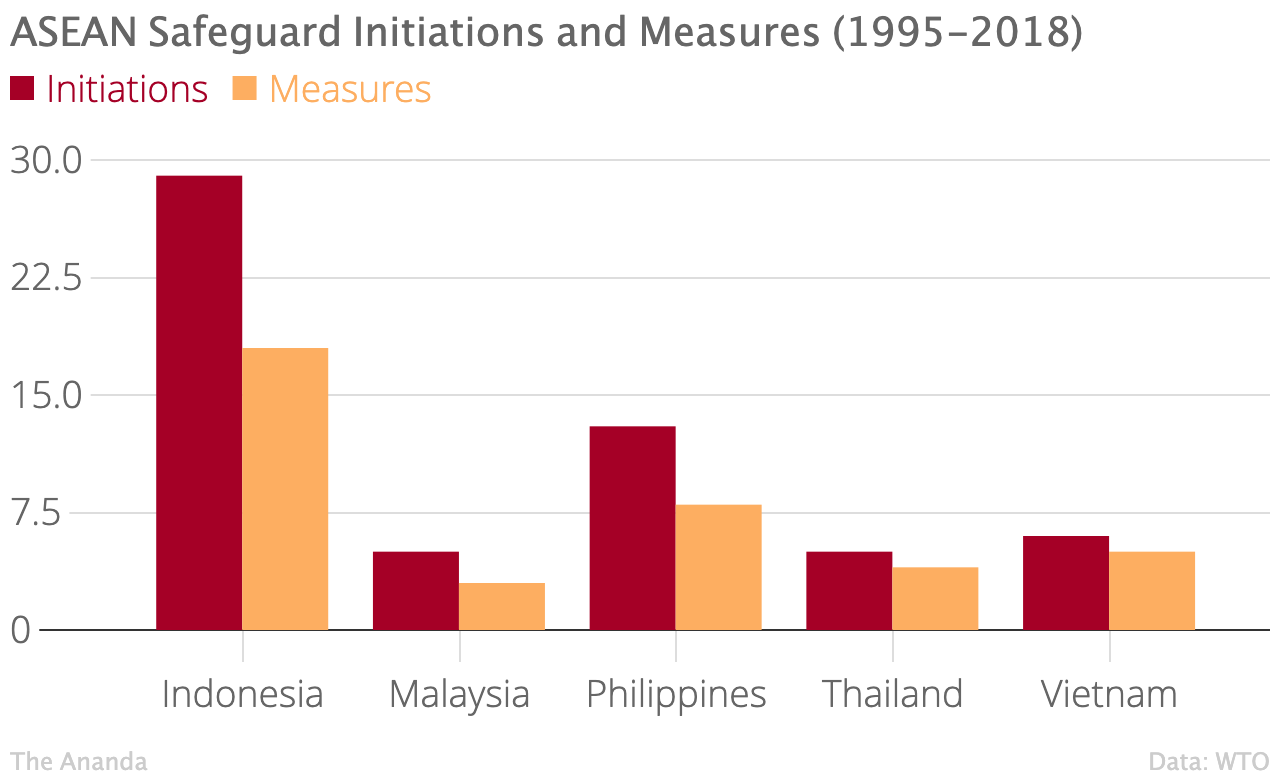

In the WTO’s language safeguard ‘initiations’ refer to the launch of the process for taking safeguard measures, and ‘measures’ refer to the remedial action being taken. Across ASEAN, six countries have a safeguard law and the numbers of initiations and measures reported by the WTO are shown in the chart below.

Safeguard Bill

According to this draft law, the main bodies responsible for safeguard measures are the ‘Prevention of Import Increase Committee’, the Department delegated by the Ministry of Commerce, and an investigation team.

If a domestic producer reports that harm is being caused by an import increase, the Department will examine whether the evidence meets the requirements within five working days and report to the Committee. The Committee must then decide whether the evidence warrants a continuation of the examination, and if necessary, an investigation team will be appointed to look further into the case.

Urgency to address damage being done to domestic producers can be established if there is evidence the import increase is making their survival difficult. If this is found in the report of the investigation team, a temporary safeguard tax on the import goods may be recommended to the Committee, which can then impose a temporary safeguard tax for a maximum of 200 days, in accordance with WTO rules.

When determining whether domestic producers are harmed or threatened, the investigation team must consider changes to the amount and price of import increase, the domestic market share of the import, and other general conditions in the market including sales, production, productivity, profit and loss, and employment. If harm or threat to domestic producers is detected, a safeguard tax, the restriction of further imports, or both, can be imposed on the good concerned.

A safeguard measure on one kind of good can be in place for four years, but with extensions can go up to ten years. Extensions can only be applied by the Committee based on evidence of improvements by domestic producers.

The investigation team must review the safeguard measure from time to time, and in the case of measures lasting longer than three years duration, there should be a mid-term review, with recommendations made to the Committee on whether to continue, reduce or stop the measure. According to the bill, Myanmar is obliged to comply with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the Safeguard Agreement (1994), other World Trade Organisation agreements, and any other relevant international or regional Agreement.

To be considered

Myanmar is in the process of drafting bills for other trade remedies – namely anti-dumping and countervailing measures – and is awaiting the WTO’s approval and technical advice. The safeguard bill is therefore the first of three trade remedy bills to be submitted to the Hluttaw, which provides an opportunity to consider the following:

Revenge

Unlike other trade remedies, there is a possibility that if Myanmar takes safeguard measure, an exporting country could seek revenge by imposing import levies on Myanmar goods, for example. If that happens, this may harm other trade sectors. Tit-for-tat trade wars can be significantly harmful to economic development.

Informality of the economy

Another consideration for the government is that a large proportion of Myanmar’s economy is in the informal sector, especially SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises). This means businesses are often not formally registered, operate outside the jurisdiction of the state and seldom pay taxes.

Clearly, businesses operating outside the purview of the state will not be able to report harmful import increases. Unless they formalise, trade remedies will be of little benefit. The need to formalise the economy in Myanmar is a well-known challenge and may require government to make some concessions to business to reduce restrictions and requirements for SMEs. This is a difficult balancing act, as it needs to be done without compromising workers’ rights and within the overall need for government to raise significantly more taxation. In general, however, it would be of significant benefit to SMEs to be protected from the potential harms that can be done to their businesses from the increase of imported goods.

The Ānanda

The Ānanda